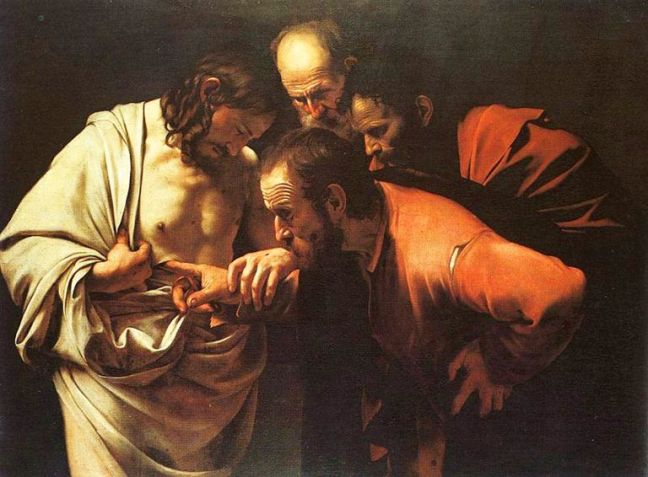

The 3rd of July is the Feast of Saint Thomas the Apostle. “Doubting Thomas,” as he is commonly known, gets his moniker from his refusal to believe that Jesus has risen from the dead. “Unless I see the marks of the nails in his hands and put my finger into the nail marks and put my hand into his side, I will not believe.” (John 20:25)

I always thought that Thomas gets an undeservedly bad rap. When someone is labeled a “Doubting Thomas,” it is usually not a term of endearment for their healthy skepticism or their careful mind, but instead a mocking nickname for their stubborn refusal to acknowledge an apparent truth, or their tendency to produce objection after objection in an effort to dispel what is obvious to everyone else. One can almost see Thomas with his arms folded, impassively shaking his head (and perhaps even stamping his feet) as he rejects the testimony of his fellow disciples. And one can perhaps imagine the disciples chuckling to themselves when Jesus appears and tells Thomas, “Put your finger here and see my hands, and bring your hand and put it in my side, and do not be unbelieving, but believe.” Thomas, chastened, responds, “My Lord and my God!” Jesus then seems to chide Thomas: “Have you come to believe because you have seen me? Blessed are those who have not seen and have believed.” (John 20:27-29) Silly Thomas! How little faith he has! This was the image I had in my mind as a child when I first heard this story, and though it was certainly a caricature, it stuck.

But, if we stop and think for a moment, this caricature makes little sense. Thomas is unlikely to have stubbornly folded his arms like a spoiled child. He had just lost one of his closest friends to a grisly death barely a week before. John’s Gospel relates how Thomas urged the disciples to return with Jesus to Judea upon the news of Lazarus’s death, knowing full well the risk to Jesus’s life and their own lives at the hands of the Pharisees (“Let us also go to die with him.” John 11:16). How did Thomas feel knowing that he himself lived even though his Lord and friend had suffered and died? He was certainly in the throes of deep mourning and wracked with guilt, perhaps haunted by the bravado he had shown earlier when he had declared his willingness to die for Jesus. Like the other disciples, I imagine that Thomas had high hopes that Jesus would usher in the Messianic Age in his own lifetime, leading an army to drive out the Romans and restore Israel’s sovereignty. The death of Jesus—and a deeply shameful death at that—seemed also to mean the death of Thomas’s own dreams. Thomas was a man who had put all his eggs into one basket, and it now seemed as if the world had seized that basket and unceremoniously hurled its contents off a cliff.

So, when the disciples tell a grieving Thomas the incredible news that Jesus has risen, I can imagine that he is not yet ready to accept it. His own wounds are too fresh. He cannot bear to stir the embers of his fading hope only for them to be extinguished altogether. For Jesus’s resurrection to be anything other than his friend and Lord truly come back to life would be too much—a twist of the knife, a macabre teasing of the bereaved. Imagine burying a loved one and hearing a friend tell you that that person has come back to life. How could it be anything other than a cruel joke?

Critically, though, there is a part of Thomas that wants to believe that Jesus has risen. He does not say, “It is impossible! Don’t speak such nonsense! The Lord has not risen!” After all, he witnessed first-hand Jesus raising Lazarus from the dead. There is reason to hope, even if hope is a hostage to fear. Though Thomas fears having his heart crushed by disappointment again, he is willing to open it a crack. Hence, he admits that he would be convinced if only he could see Jesus alive with the marks of his crucifixion. That’s all Jesus needs. Just as He entered the locked Upper Room to comfort the frightened disciples, so too did He enter Thomas’s wounded heart to reassure him. Jesus knew Thomas’s heart; Thomas was not trying to test God. He wanted the resurrection to be true, but like an injured child who craved the reassurance of his mother, he needed God’s reassurance. Thomas sought the faith that would allow him to believe in the risen Lord, and as Jesus promised in Matthew 7:7-8, he found what he sought. Tradition holds that “Doubting Thomas” became one of the most peripatetic of the Apostles, bringing the Good News of Christ as far as India, of which he is now patron saint. Clearly, whatever pain or doubt Thomas harbored before he met the risen Christ was replaced by a great inner peace and fearlessness.

What Thomas can teach us, I think, is that our faith need not be perfect. The desire to believe in Jesus is enough for the Holy Spirit to plant the mustard seeds of faith within us. This is the key difference between Thomas and someone whose skepticism is aimed at dispelling religious belief. The former seeks in order to find; the latter is only interested in finding evidence that the whole search is futile. All of us struggle at times with the belief that God is indeed always with us and that He indeed loves us. Suppose that we could be convinced of that, not just intellectually but deep within ourselves. How would our lives be different if we were freed from all fear? What marvelous things would we dare to do? If we can imagine and earnestly desire that faith, freedom and inner peace, then I believe God will grant it to us, just as he did to Thomas. Would that our doubting be like Thomas’s!

-Class of 2003

“[H]e is willing to open [his heart] a crack…[t]hat’s all Jesus needs.” Love this. My spiritual life is basically me with my fingers in my ears (LALALALALA I CAN’T HEAR YOU) and God trying to convince me to take the fingers out briefly, or occasionally shouting loudly enough that I can hear Him anyway. Following with an entirely open heart seems unattainable. But maybe “just a crack” is a goal within reach. Something to strive for!

-AMD

LikeLike